Our Return to Good and Evil

Twin Peaks Against the Shakespearean Quincentenary

Something was unearthed during the pandemic. Our corruption, the result of a process of disorientation that was sown some five hundred years ago, ended sharply in a quake of fear when we sensed its emergence.

In some sense the Event didn’t take place. But the one that could have happened, the pandemic of our premonitions, was enough for us. The ease with which we succumbed to it was even more alarming. While the pandemic robbed the world of two years and an incalculable amount of cultural momentum, we can thank it for reviving our cognizance of the darkness.

Some of our brighter minds, like Giorgio Agamben, immediately tipped their hats to the conspiratoid masses for their grand insight. In fact, Agamben was so early to the discourse that it’s perhaps more accurate to say he is a member of those masses.1 Our dullest minds, like Yuval Noah Harari, whole-heartedly championed the other side of the equation, and poured gasoline on the theorists’ minds with comically grotesque visions for future Events.

Our bearing witness to these visions accelerated our departure from the haze of Machiavellianism. Was it solely because of the visions? Or was it because the pandemic, increasing the hurt in the world, shoved people back into unfortunate domestic situations and set back their development? Either way, we will never again be able to look with a purely Nietzschean eye at the world, viewing human corruption as passing clouds. Man is not a system; there is an evil out there lurking, not a substance as the theologians thought, but a negative mood-attunement.

We, as a culture, were poised to once again recognize evil’s existence, with philosophers like Alain Badiou and Simon Critchley heralding its return in the early 2000s. But our return is a return to the concept, not the substance: ours is not the same as the one of the tradition. The “evil” of the past concerned naughty transgressions, follies of immoderation at the individual level, “sin” or ἁμαρτία in Koine Greek meaning ‘to miss the mark’ (the Hebrew חָטָא or “chata” has the same meaning). Or, evil referred to the abuse of power by local, petty lords and bandits roaming in the wilderness; such evils led to the corporeal misery of God’s flock.

Today, evil is not so basic and obvious. Our therapeutic culture has noted such follies for what they are, follies, and categorized them under self-destructive behavior. Our technologically sophisticated economies have increased the amount of wealth in the world and lessened the need for such banditry. This evil is more oblique: it occurs at the level of language, wearing down our moral senses until the uncanniest of guests is invited. It is a kind of nasty mendacity, where the infected destroy their self-worth as much as they destroy others’. It is a verbal sabotage of creation before it becomes an enacted one, and thereby grants for itself a distance from the divine not previously accessible. In this sense, it is far more horrifying, because it is suprahuman. And because it is nowhere in particular, and cloaks itself as gentle nihilism, it rebukes all forms of self-righteous certainty: to be good, you must accept the weirdness of the world.

Nothing I am aware of advances this oblique theory of evil as well as the three seasons and two films that make up Twin Peaks. It predated these philosophers in surpassing the postmodern condition: it moves past amorality without succumbing to tradition. David Lynch and Mark Frost’s world is full of wounded people who cross over to the “hell hole,” to use Lynch’s parlance, a darkness that exceeds any conventional notions of evil like political oppression or sensual immoderation.

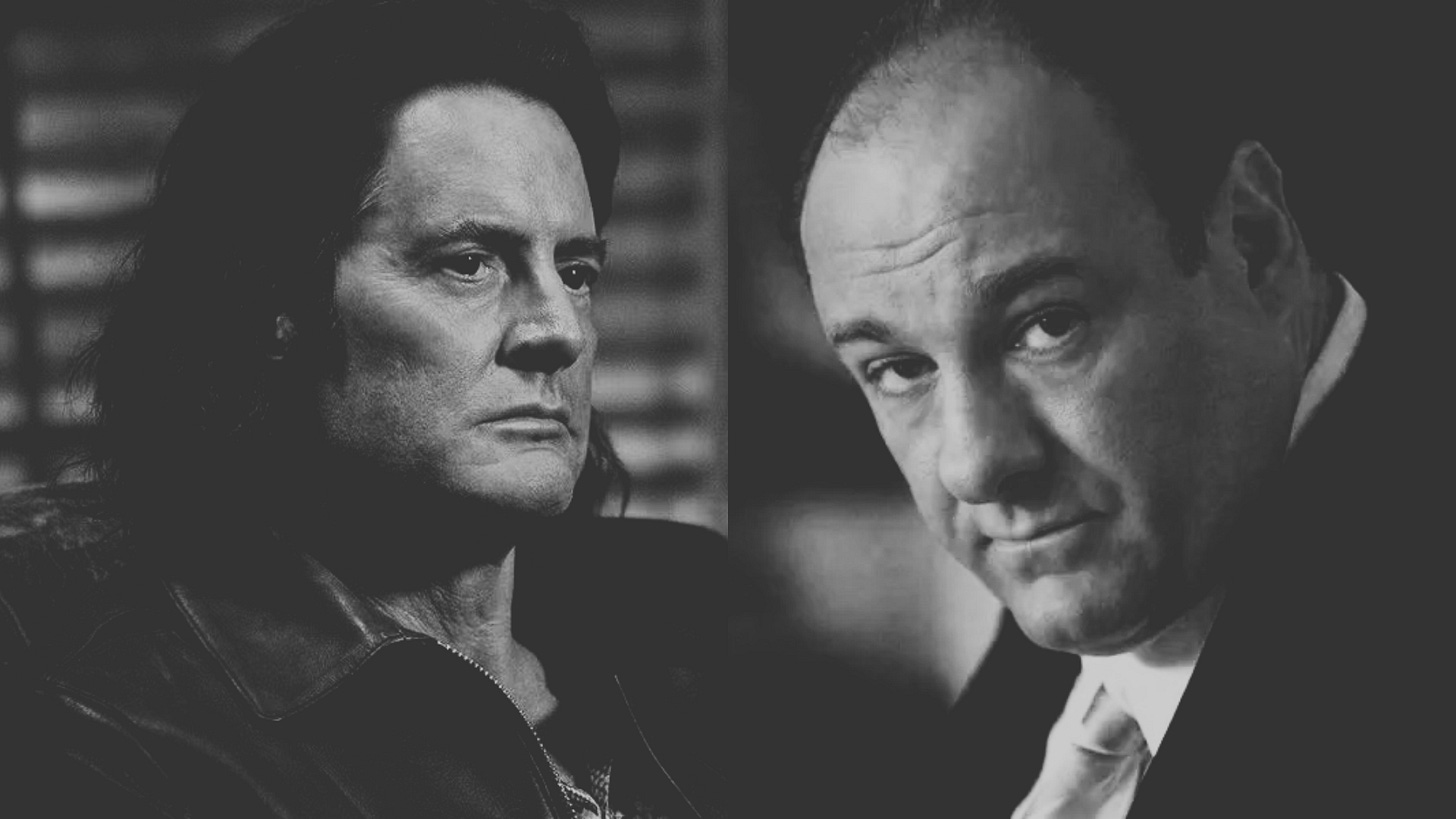

In this sense, The Sopranos, as good as it was, was a moment of twentieth-century twilight, a holdover from the Shakespearean quincentenary.

This essay is strictly a literary affair. If the concept of evil has returned, that is good, because we are in need of plots. Enough with the doldrums of social commentary, which vaguely gestures in eventless stews. I will be articulating an argument for the existence of absolute, singular evil, as well as an absolute (but inherently plural) Good, with the purpose of cultivating polarization for dramatic plots. This essay may bear forth conclusions in you with real-world ethical, political, and religious consequences, but I can’t be blamed for that.

Inferno

In Twin Peaks, there are tiers to the terror haunting the world. The evil is rare and is slumbering until it is awakened by great fear. Men, when they become corrupt, are conduits of great evil. Those whom it possesses have already prepared the harbor for the demons’ landing; a corrupt soul lets its celestial guard down like a bribed city watch. Evil, especially in The Return, is summoned to the ubiquitous corruption of the 2017 world to feed on human suffering like a cockroach feeds on garbage.

BOB, in the form of Leland, helped foment the corruption visiting the town through his work with Ben Horne and the den of One-Eyed Jack’s, from which pours out all sorts of destruction, whether trafficking girls from the perfume counter or helping the Renaults and Leo sell drugs. BOB, in the form of Mr. C with his pitch-black eyes, gathers together all the sleazy elements of rentier capitalist society and mobilizes them toward hits and other unnamed criminal enterprises. The town of Twin Peaks in The Return is utterly beset by a drug epidemic plaguing its youth. It is being facilitated by Red, the boyfriend of Shelley, and Richard, the sociopathic son of Audrey and Mr. C.

The criminal types are not pure evil, but corrupt, morally neutral and relativistic. Corruption is an earthly form of evil: it is the Seven Deadly Sins of tradition. These sins beckon the evil, but are not itself the evil. Lynch’s point is manifestly not to lecture and harp on about the intrinsic villainy of vice—drugs, sex, gambling and so on—but to say that these activities, especially when wrapped up with organized crime, have the tendency to spill over into murder, abuse, and eventually a state of egomaniacal power tripping which invites the demons.

Compare that to the scene in the utterly secular universe of The Sopranos where a “mob expert” delivers a line on the news something to the effect of: “so long as men have appetites for vice—gambling, pornography, drugs—there will be a mafia.” The Sopranos follows the long tradition of modern political philosophy, which stretches back to Machiavelli and even further to various tyrants and sophists of antiquity. While the show makes note of Tony’s psychopathic nature, he is ultimately an anti-hero whom viewers are made to celebrate as he deals with the incompetence of fools. The basic claim is that the notion of the Good is a utopian pipe dream, while the notion of pure Evil is a scare tactic from the priests: in our corrupt world, we must pursue a path of harsh pragmatism to obtain a semblance of the good life.

Under Machiavellianism, corruption is viewed as a casual thing: a shrug of the shoulders, “what can you do,” “it’s a dog eat dog world out there,” “a man’s gotta eat,” “They do it too,” etc. Chantal and Hutch, the two hitmen in Mr. C’s employ who always eat fast food, are perfect examples of this type. Chantal guiltlessly murders the Vegas hitmen, people in her own world whom she probably knows, on behalf of C for their failure to kill Dougie. During one scene, Hutch says to Chantal that the U.S. government is murderous too, justifying their careers as paid murderers through relativistic logic. They don’t understand who C is, “what” he is; the Evil is completely beyond their comprehension. But they dutifully serve It because they are alienated from the Over-Soul.

Machiavelli wrote in The Prince: “How one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live, that he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation.” Leo Strauss believed this idea is the foundation of the entire field of “political science,” the principle of liberal societies, and the distinctive trait of the modern man. Paraphrasing Machiavelli, Strauss wrote:

Let us then cease to take our bearings by virtue, the highest objective which a society might choose; let us begin to take our bearings by the objectives which are actually pursued by all societies. Machiavelli consciously lowers the standards of social action. His lowering of the standards is meant to lead to a higher probability of actualization of that scheme which is constructed in accordance with the lowered standards. Thus, the dependence on chance [fortuna] is reduced: chance will be conquered.2

By transforming philosophy from a pursuit of the Good into a field manual for programmatic social engineering in the service of utilitarianism (or the least the reduction of suffering for a specific class or race), the modern philosophers forsake the ethical demand and redefine man as a machine. From Hobbes to Marx and Nietzsche, these thinkers pursue Machiavelli’s insight that fortuna can be controlled to its end, declaring that humanity itself is a system. Certain behavioral results will occur if the right inputs are administered. The most radical expression of this was Anti-Oedipus, a book in which the voices of the May ’68 generation revive 18th century mechanist Julien Offray de la Mettrie, this time using the hydraulic vocabularies of Freud, Marx, Nietzsche, and Spinoza rather than enlightenment deism, terming humans “desiring-machines” who need to desire even harder to obtain full communism. But if mankind is a process, this will all just happen or it won’t; there’s no sense in persuasion or moral intervention. In this sense, Kantian academic Omri Boehm remarks that Spinoza’s choice of the title “Ethics” for his book must have been a joke.

When the administrative authorities have increasingly suppressed their natural intuition and built up their rational faculties, they are unable to resist the sadist temptation when it arises. Snide reason can rationalize anything.

While the Twin Peaks universe seems to agree that corruption is endemic to creation, the picture it paints of the crime world is different from some mafia servicemen merely working to fulfill the demands of the black market. These criminals feast upon pain and poisoning; they, under the influence of the demons in the Convenience Store, laugh with terror as they burglarize their own grandmothers like Richard Horne. How precious does Shakespeare seem when compared to the abyssal evil of Lynch? Lady Macbeth, intended as the most egregious power addict of all time, is as tame as Carmela Soprano on a bad day. The dynamics of mass society rapidly invent terrors beyond Shakespeare’s imagination: mustard gas, gatling guns, drone warfare, cellphone bombs, pedophilia operations. Our return to good and evil is nothing less than the moving out of the shadow of Shakespeare. If Harold Bloom was right that Shakespeare invented the human, with Twin Peaks we exit humanism into something else.

While evil begins with the mere nastiness of unsavory types, it festers and grows until it becomes a walking monster of ungodly power. This repulses us, as it did to Ben Horne, and we recoil back into the infinite unfulfillable demand of the Good.

In Infinitely Demanding, Simon Critchley recounts how in the 18th century Francis Hutcheson failed to ground his claim that benevolence was universally understood to have superior moral worth. Adam Smith noted there was a disconnect between subjective moral ideals and the practicability of acting on such principles. Critchley suggests this distinction makes “morality” itself an incoherent concept, because an ethical code that is not felt to be demanding by the subject is meaningless.3

Instead, Critchley argues that any coherent philosophy of ethics must be heteronomous—having its source in the Other—rather than autonomous, emanating from the actions of the self. From Badiou, he takes the notion that the subject “commits itself in fidelity to the demand that opens in a situation but in a manner which exceeds that situation in the direction of universality.”4 From Knud Ejler Løgstrup, he takes the notion “of what he calls ‘the ethical demand’ and his emphasis on the radical, unfulfillable and one-sided character of that demand and the asymmetry of the ethical relation that it establishes,” using Matthew 5:43-8 as an example. where Christ preaches that we love not just our neighbors but our enemies too.5 From Levinas, he takes the notion that this infinite demand of the Other splits the subject between itself and the unfulfillable demand;6 Critchley adds that this split must be healed through art.

When we remove external demands of responsibility, notions of pure evil and good, and make morality a matter of reasoning (whether sentimental in the case of Hume or critical in the case of Kant), we gradually erode the foundations of moral confidence until society dissolves and the deep, vicious evil wakes up. The personal power-grabs you think you are committing are illusory. This evil morphs into sadistic caprice against the innocent, wielded by Control. And this, not content with the natural limitations of man, ineluctably seeks to supplant hominid subjectivity with machinic subjectivity, that is, to grant Gestell (technological enframing) with as much free space for rapine and resource-mobilizing scandal as possible.

There are three tiers of evil in Twin Peaks: Judy, the dwarf, and BOB. Their desire appears to be the extraction of pain from human beings and the eventual destruction of the world in a way that forecloses its redemption.

There is Judy, who to our knowledge is the source of all evil, an “extreme negative force” which was known in antiquity as “Joudy”7 but who came back with a vengeance at the dawn of the nuclear age.8 When Mr. C asks Jeffries who Judy is, he tells him to ask her himself and gives him a series of numbers that match the librarian’s coordinates that led to Twin Peaks. If the demon-possessed Sarah Palmer is the host of “Joudy,” it would explain why a shroud of evil seems to hang over the town in The Return.9

Then there is the dwarf, also known as The Arm, who is the gatekeeper of hell.10 In The Arm’s employ are BOB and formerly MIKE, the latter of which is a figure of chaotic neutrality verging on goodness. At the end of the FWWM, when BOB returns to the lodge after Laura’s death, the dwarf and MIKE say in unison, “I want all my garmonbozia [pain and sorrow]!” Their activity amounts to arational, sadistic caprice—pointless, ravenous cruelty—which goes beyond the logic of sin, material corruption, or immoderation. It has no teleology; it wants to feast on suffering, with the ultimate kind being the hijacking of the apocalypse.

Evil takes passions, which are good and Natural, and twists their use into pain and destruction, which stems from anti-nature. In his hymns, Hölderlin fuses Christianity with the paganism of classical Greece by divining that Hercules and Bacchus are Christ’s brothers. Christianity, super-naturalism or the ethical capacity, stands with the naturalism of the gods and the body against the anti-nature of Satan and world technology. In his commentary of his Oedipus Rex translation, Hölderlin writes: “the representation of the tragic is mainly based on this, that what is monstrous and terrible in the coupling of god and man, and the total fusion of the power of Nature with the innermost depth of man, so that they are one at the moment of wrath, shall be made intelligible by showing how this total fusion into one is purged by their total separation.”

A diagram of this can be drawn:

Christ – Supernature – Love, sacrifice

Pagan – Nature – (self-em)power

Satan – Anti-nature – Wrathful, lack, lust for control

To vanquish evil, Hölderlin thinks man needs to go back to his proverbial home; his proper dwelling is in poetry; poetry is alighted when it finds again the places—rivers and lands and mountains—it called home in the first dawnings of its languages. But the very idea of home is at risk of being eviscerated by the weightless transitoriness of desirous technopower.

Harari’s books, such as Homo Deus, spell out a world in which all borders, languages, cultures, and laws evaporate, replaced by a transhuman technoid species that supplants God and engineers its own genetic code. But the obliteration of such essences means the obliteration of all memories, past and future, making time itself, Chronos, meaningless. Besides the sheer hubris of this thought, which is blasphemous to both Christianity and Greek polytheism, it would be an act of self-defeat: without any of the strictures of place, duty, or respect for the other, our lives are utterly without meaning.

In Heidegger’s late work, Physis, Anfang, “Nature” means the conditions and limits imposed by “Cosmos”: order, the external source of limitation which is not equitable but it is fair. The heart of Machenschaft/Machine, on the other hand, is to remove all conditions in favor of infinite striving—but striving is nonsensical and incoherent without conditions. Action would become a brain melting in on itself, willing without reason, floundering in the abyss of nihilism, clinical insanity as the law of the world. Freedom from nature and history is slavery to the Algorithm. Total domination of nature, world-control as the Final Solution to the human problem, is BOB’s sadistic caprice on a cosmic level. Sadistic caprice has as its logical conclusion the downfall of the species, qualitatively in the form of slavery or existentially in the form of nihilistic anti-natalism.

As Heidegger demonstrates throughout his works, this form of domination is synonymous with World Technology. Technology, with “will to will” as its metaphysics, wants total Control, unlimited subjective power over nature. But in olden times this unboundedness was simply, chillingly, called The World. All the kings of the World fornicated with the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation, just as all the kings of the World fornicated with the World Economic Forum and the World Health Organization during the pandemic, blitzing the populace with fear to attempt mass looting and global slavery. This would be the triumph of what was previously called the satanic. The tradition was right to call this evil because, as we saw with Critchley, evil is that which disrespects the reality of the other’s interiority, shirking heteronomous responsibility.

Such sadistic caprice is most associated with the cultural image of Satan. The figure of Satan did not always have this character, of course. In the Old Testament, he is mentioned as “the accuser” (ha-satan). In The Book of Job he is seen accusing God of lack of faith in his own system, wagering that his most devoted follower will turn his back on him if he suffers outrageously bad fortune; God gives in and performs the experiment. The radicality of this notion is still palpable: that not even God is above the seductive appeal of transgressing his own self-imposed conditions.

Satan is mentioned in the Gospels as “the tempter” to whom the Holy Spirit brings Christ after He is baptized. According to Saint Matthew, the ultimate temptation Satan offers, after the temptation of bread and the temptation of testing God and his angels, is power over the kingdoms of the world. “Again the devil took him up into a very high mountain, and shewed him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them. And said to him: All these will I give thee, if falling down thou wilt adore me. Then Jesus saith to him: Begone, Satan: for it is written, The Lord thy God shalt thou adore, and him only shalt thou serve.”11 This is roughly the same temptation Goethe gives to Faust: by the end of Faust II, the former scholar had become so obsessed with gaining power that even Mephistopheles feels exhausted. Right when this Napoleonic occultist bullies an elderly couple off their land and points greedily over to the one last patch on earth he hasn’t claimed, hell opens up to grab him; he is saved by the angels, the transporters to the intransitory Eternal Feminine, who sing: “for him whose striving never ceases / we can provide redemption” [Wer immer strebend sich bemüht, / Den können wir erlösen].12

Purgatorio

It’s not that evil is everywhere—we don’t have the license to start claiming everyone we meet could be evil, thumping our chest like a limp-wristed Neocon. It makes sense that we initially moved away from the concept of evil; the witch hunt mentality and arrogance to denounce it engenders is foolish and dangerous. If we are allowing the thematic “evil” to return to our discursive fold, we are doing so with the admonishment that it remains seldomly invoked but always vigilantly watched for, a fire extinguisher to put out the blaze of self-crippling neutrality. Twin Peaks is certainly not a simple morality play where X is what one does to be good and Y is proof that someone’s very substance is evil. The wish for an absolute, infallible knowledge of the Good, and a clear roadmap for achieving it now and in every future situation, is a covert evil because it is a desire to transcend finitude and time and become God. We must accept our humanly state.

According to the logic of Twin Peaks’ plot, sex before marriage is not a problem, and adultery isn’t intrinsically wrong—but divorce isn’t inherently good, either. In the couples of Leo Johnson and Shelley, Catherine and Pete, Norma and Hank, Ed and Nadine, Snake and Donna, we find that the pursuit of proper love outside of the established failed relationship is really a fight for bliss against the corruption infecting it. All the corrupt actors that in some way led to the death of Laura Palmer are specifically corrupt in the way they relate to the other sex. Corruption is spawned from lovelessness. Meanwhile, the White Lodge is summoned by great love.

This evil is not what the tradcaths would fixate on as evil. It’s not “licentiousness” or gluttony for sex, power, money, substances, food, per se. Twin Peaks is not a show about vague “good morals.” If Season Three: The Return is about the collapse of American life, Twin Peaks Seasons 1 and 2 were a commentary on ‘60s morality and divorce.

Lynch is Blakean in that he thinks consensual sexuality and desire is truly on the side of God,13 but the redemption of the body does not lead to a relativism and a corruption of the ethical faculty—in fact it emboldens our defenses against Evil, because it takes away one of Evil’s prime bargaining chips, the temptations of the flesh. Desire itself is not evil, but the Satanic obsessive acceleration of desires toward abolitionary ends (Deleuze and Guattari) is. Evil thinks it will gain unlimited control and pleasure, Thelema, but it will actually only beget injury for its practitioner, because what we really want is love, to fulfill our responsibility to the other—which cannot be achieved through loveless action.

If this is the case, then Lynch stands in direct opposition to the First Epistle of John, which warns against the “three evil things”: “concupiscence of the flesh, and the concupiscence of the eyes, and the pride of life.”14 Nietzsche re-baptizes these as “sensuality, the lust to rule, and selfishness,” and reinterprets them as the three virtues of the Übermensch.15 Nietzsche is right to critique these—unless another reading is possible. Perhaps the way we must understand it is as Saint Francis and Julien of Norwich did: that matter is not evil, that God sends us into the world to wholeheartedly embrace it in absolute wild abandon, to become fully of it, not to get caught up in its objects but in order to pass by it and overcome it, and in fact pull it up and transfigure it, levitate it back up to paradisal golden perfection.

In Aristotle, form is the male and materiality is the female. The Satanic, in this reading, is anti-feminine because it is the pure Will rebelling against conditioned nature. And we all know how much Lynch loved women.

“Free love,” on the other hand, is a contradictio in adjeto—as Badiou argues, true love must involve a “fall,” a moment of infinite vulnerability, as opposed to the dating apps that promise “love without a fall.” Or as Zizek says, true love cannot be universal love of man—that is an empty abstraction; true love is love for another person in the flesh, whom you take and say to the rest of mankind “fuck you.”

“True” here is being used, as Critchley articulates, in the sense of treu in German or “troth” in archaic English, in the same sense that Christ refers to Himself and his way as the truth—it means fidelity, loyalty to a demand.16 It therefore cannot be achieved in the lax concession-making tepidity of free love, the love of Hutch and Chantal. Twin Peaks is not against physicality but against lovelessness: violence, rape, child abuse.

Nietzsche argues that the sole purpose of the family is that it guarantees the reproduction of human beings. But the crucial aspect of the family is that it, properly conducted, it guarantees the proper raising of future human beings, the spreading of love and the elimination of lovelessness. This is for the same reason as Zizek’s point, because we can only have Truth where we find sacrifice and fidelity, cost, not in a free-for-all.

The Good I am describing is not benign and submissive, but the kinds that found new regimes in resistance to old corrupt orders, as Cooper does when he challenges the town’s establishment and resists the FBI as it strips him of his badge. His “New Age” Transcendentalist morality drills down past the tradition to the real heart of evil, just as it gets to the real heart of Good.

What I offer to Critchley is that we use Heidegger’s thought on mood here to provide an account for the “material” origin of evil and good. While Critchley’s ethics, via Levinas, are entirely existential, being rooted wholly in a heteronomous relation to the other rather than in a World of Forms, there still has to be some description of what good and evil are. Without that, we just have relationships with some sentimental terms thrown in, a kind of Humean existentialism. I propose we conceive of evil as Being and Time’s notion of stimmung, meaning both mood and attunement.

It is a brilliant notion: it thinks of mood as something out there, not produced by our psyche but really there in the world detected by pre-categorial intuition; it gets beyond the subject-object dichotomy, without asserting that such moods are ontological substances or ideals, analyzable by reason and capable of being computed. Evil is a singular, external mood-attunement of negativity, triggered when Dasein’s proximity to the will to will has grown overpowering. Its vaulting ambition o’erleaps itself and falls on th’ other. It has no logic, and only wants “garmonbozia.”

Good, on the other hand, is the mood of ecstatic joy, “idiot glee.” Or what Lynch calls “total bliss.” As I argued in my piece on the Halcyon, there is another way of thinking about quality, which does not measure actions according to how they live up to ideals but measures settings according to how they live up to tones. One could say the good is the Halcyon. This would be inherently plural, because each individual has unique access to the total bliss and because tones can combine in infinite permutations. Once felt, the Good pulls us to act like the those in Plato’s allegory of the cave, who bring it to down to others—but it is not a concept, only a sensation. It is therefore best communicated not through dialectic but through art.

Nietzsche’s incessant use of “immoralist” and his praise of “evil” has tripped us up. Nietzsche doesn’t trip himself up as a philosopher—he opposes Life against ressentiment while maintaining a monistic universe, since ressentiment is a form of will to power—but he certainly trips up poets inspired by his work. As much as Nietzsche protested Plato, by working within his genre or discursive mode of Unity or monism—philosophical thought inherently trends toward this—Nietzsche was far more Platonic than artistic. Nietzsche’s attempt to turn Life into a form of ethical normativity, and his transfiguration of his philosopher-sketches into archetypes in Zarathustra IV, performs this to a degree, but this all stands in direct contradiction to his cosmology of becoming and power. Alain Badiou in Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil (1998) makes a full-throated defense of the concept against Nietzsche, writing: “No life, no natural power, can be beyond Good and Evil. We should say, rather, that every life, including that of the human animal, is beneath Good and Evil.”

No poet or any other kind of creative artist has been solely Nietzschean. The artist needs extreme types to furnish a story, and needs to come to a point in his story where one type succeeds or fails against another, rather than an all-accepting totality of immediate, universal, amoralist redemption.

Rather than conceiving of art with Nietzsche as the affirmation of naturalism, Critchley thinks of art as a reparative job for the wound that the infinite unfulfillable demand from the wholly-Other rips opens in us, art as an act of sublimation of this pain. Comedy is better at this than Tragedy because it allows the superego to laugh at the ego (taking a cue from Freud’s On Humor), thereby allowing us to take the guilt of non-perfection off our selves and press on with ethical deeds anyway.

Will society collapse into family evisceration without the subordination of plots to orthodox religious messaging, whether the Church or some other moral institution? No, the Supreme Fiction will stand in for it; through its aesthetic-moral qualities, and its accurate capturing of evil rather than the church’s black-and-white tabulations, it will repair the ethical split.

Paradiso

But where is the Good in Twin Peaks? Chiefly with the Giant, or the “Fireman,” the one who initially helps Cooper discover BOB. After the scene in Part 8 where The Experiment vomits BOB, it cuts to an ocean with a white brutalist spire built on a colossal rock formation—the White Lodge. The teapot via projector shows the Fireman the nuclear explosion, the Woodsmen at the Convenience Store, and BOB’s birth. The Fireman then levitates, lays flat as calming music plays and produces amberish-gold light. The light shapes into a large canopy and then shoots out an orb. The orb flies down to the lady, possibly the Fireman’s wife, who grabs it and discovers it contains Laura Palmer’s face. She kisses the orb. The orb then flies off toward America. (Just before the death of Margaret Lanterman—the “Log Lady” whose log whispers secrets to her—she calls Hawk and tells him her “log is turning gold.”) In response to the evil of Joudy, the Fireman impregnates his wife with a child who will set in motion a quest to fight against it.

To destroy yet another tenet of postmodernism, let’s look at David Lynch’s life and thought to make sense of his art. There is an anecdote from Mel Brooks about first meeting with David that instantly captures his art—the normal surface with terror underneath: he expected a “young Max Reinhard” or “a Picasso with two eyes on one side of his nose” and instead got this cleanly-dressed Midwestern kid, “a young Charles Lindbergh.”

A quote from David explicates how this was also the case for his childhood, spent mainly in the Pacific Northwest but in North Carolina and Virginia as well:

My childhood was elegant homes, tree-lined streets, the milkman, building backyard forts, droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees. Middle America as it's supposed to be. But on the cherry tree there's this pitch oozing out – some black, some yellow, and millions of red ants crawling all over it. I discovered that if one looks a little closer at this beautiful world, there are always red ants underneath. Because I grew up in a perfect world, other things were a contrast. (Lynch on Lynch, 2005, p. 10-11)

While studying painting in Philadelphia, Lynch moved his first family into the city’s Fairmount neighborhood where they bought a house for cheap due to the high crime rates:

We lived cheap, but the city was full of fear. A kid was shot to death down the street ... We were robbed twice, had windows shot out and a car stolen. The house was first broken into only three days after we moved in ... The feeling was so close to extreme danger, and the fear was so intense. There was violence and hate and filth. But the biggest influence in my whole life was that city. (Lynch on Lynch 42-43)

In his book David Lynch: Beautiful Dark, Greg Olson drew a contrast between Philly and Lynch’s childhood in the PNW, suggesting it gave him a "bipolar, Heaven-and-Hell vision of America.” One critic noted this recently in their obituary, saying his narratives “pit exaggerated, even saccharine innocence against depraved evil.” Another claimed he was a “a religious or spiritual artist” whose films follow the metaphysics of “India Vedanta” with some American Gnosticism thrown in à la Harold Bloom.

In March 2024, Lynch went on a podcast to discuss Transcendental Meditation, a lifelong obsession of his (Lynch meditated twice a day every day for over 50 years). He talked about how anger is a weakness, and how the stress and suffering in the world—"there’s so much domestic abuse, trouble in the homes, little kids feel this, and the parents, the people are y’know struggling for money and both parents are working and it’s just a hell hole, and all this road rage and plane rage and all sorts of stuff come out”— stems from people’s inability to reach the “eternal and uncreated” consciousness within all of us, which is accessed through meditation.

Lynch calls consciousness the “big treasury” of “total bliss,” and says it has qualities that we gain when we bring it to the surface: “intelligence, creativity, happiness, love, energy, power, peace.” If enough people gain access to this consciousness—just “the square root of ten percent” of the world—it would be like an “electricity plant” for peace, “a happy, creative, intelligent, loving, powerful, energetic world, at peace!”

Whereas all the practices in the modern world are about “trying hard” and “working hard,” Transcendental Meditation (which he refers to as a “technology”) is “easy, effortless, easy effortless easy effortless, no trying, and away you go… twenty minutes and you go about your business.” And finally, “you don’t go around as holier than thou or goody-goody two shoes, you just be yourself.” Just like his good characters, Andy, Lucy, Truman, and Cooper.

Lynch said some of his best artistic ideas came to him during meditation—in fact, the entire idea for Mulholland Dr. arrived this way. Cooper seems to be an idealization of himself as a human being. The Coopers of the world admire Tibet and fight against evil through dreaming powerfully. They are in touch with the inner, infinite Source of divine bliss, whereas the BOBs, locked out of it, torture others and themselves. This is the drama of our world, a battle of conscious states, where the Coopers try to uncover Joudy’s conspiracy to fill the world with suffering, brought on by those who are not at one with the world-soul. But without the depictions of the “hell hole,” the surrealistic terrors of our lives that are just as real as Saturday Evening Post pleasantries, Lynch would be a liar of an artist and a charlatan of the Source.

With Twin Peaks, the central crisis of American Literature is essentially solved. Lynch and Frost figured out a way to preserve the necessary dramaturgical components of good and evil within the anti-orthodox context of the daemonic inner spark and the over-soul. They fused Whitmanian-Lucretian flesh-love with the Gnostic warre against the damned white whale. They reconciled the culture of the ‘60s with Puritanism, revealing the former’s good and evil sides, and taking on the war against evil of the latter without succumbing to its self-righteous pomposity.

The beauty of this is that it doesn’t suggest anything unprovable, but asserts there is unchanging truth accessed through psychological practice which must be brought out and instantiated as art. This is the ethical act. If Heidegger said that the human being’s proper role is to serve as the shepherd of Being, this form of shepherding can be seen as a continual, Nietzschean striving, but one with a telos rather than Nietzsche’s amoral caprice.

At the human level, Ed and Norma reuniting is the climax of the show. Nadine digs herself out of the shit by watching Jacoby, the hippie psychiatrist-turned-Alex Jones radio host, ranting about Evil and Good (…is it a coincidence that he shares a name with Jacobi, the philosopher of Good and Evil and the man who coined the term “nihilism”? Collective unconsciousness at work). Jacoby rails against corruption in the pharmaceutical and food industries, the rot at the heart of society, but preaches an ethical response: “dig yourself out of the shit.” Political and corporate corruption is congealed lovelessness.

Whereas Cooper, by trying to remove evil at the ontological level, by reversing time and eliminating Joudy, fails. At the end of the series, when Cooper rescues Laura from her fate, altering the timeline, the camera cuts to Sarah in the 2017 era screaming and stabbing Laura’s portrait with a shard of glass, furious that they are working to end her evil. When they walk away from the door, defeated, Carrie Paige (the alternate timeline’s Laura) hears a primordial yell of “Laura!” from Sarah/Judy, the same exact “Laura!” yelled up the stairs in the very first episode. Carrie screams back and the show ends, Cooper’s mission unsolved.

Critchley thinks the “ultimate metaphysical source” of ethical obligation is unknowable by humans, likening it to a useless imaginary perpetual motion machine dreamt up by philosophers. “Instead,” he writes,

the focus should be on the radicality of the human demand that faces us, a demand that requires phenomenology and not metaphysics. To put it more paradoxically, knowing that there is no God, we have to subject ourselves to the demand to be God-like, knowing that we are sure to fail because of our finite condition—a godless subjectivation. For Logstrup, as we have seen, to fail to meet the ethical demand of the neighbor is to fail our existence irreparably. We can now see that such failure is inevitable, for we can never hope to fulfil the radicality of the ethical demand. But far from failure being a reason for dejection or disaffection, I think it should be viewed as the condition for courage in ethical action. The motto for ethical subjectivity is given by Beckett in Worstward Ho, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.17

The good must be pursued, but we cannot think that we can achieve absolute good and transcend into godhood. We must accept our finitude and our naturalness while relentlessly pursuing what Lynch Buddhistically calls “enlightenment,” or “full consciousness,” the one possession that stays with the soul after death:

No more need to be born and die. You’re immortal and no more need to die. You’re there, you’re 100 percent immortal. Full fulfilment, total fulfilment, total bliss, the whole thing you have. And it’s eternal. And this is in our future. But until then, you can only have these lives to unfold it. It can only be unfolded in a physical body. In between lives you can’t do it. So you take these bodies and bring it out.

Two Conclusions

There are two paths to take. Still persuaded by Machiavelli, we could draw the conclusion that we must attempt to work this all out in a furious battle-cry for a political-cultural revolution that would right all wrongs, produce great art like a well-oiled assembly line, and perfect the economy so that it works like a statist patron for these projects.

The other is to begin an anarchic-mystic conflagration within ourselves and spread it to others like a psychedelic napalm strike against sad passions. If “the square root of ten percent” humiliates the wrathful, the market will have no choice but to respond to the new demand.

The Angry Patron-Seeker

An early post-Nietzschean reversion to Good vs. Evil was that of Ezra Pound. In his magnum opus The Cantos, a tattered, sprawling epic that moves from Ancient Greece and Tang Dynasty China to Renaissance Italy and the early American Republic as it chronicles the story of Usury and catalogs the poisonous effects it has had on culture and human dignity. Pound equates usury with evil in the fragment “Addendum for C” as well as Time: “Time is the Evil.” More specifically, he equates usury’s imperium of nonviolence with the rotting of human quality in Canto XXX. The excremental Hell of Canto XIV, taking place in modern London, is contrasted with the heavenly, Neoplatonic light of Canto XXIX, which occupies a fictional Greece of the mind.

In Canto XLV, Pound produces a long polemic against the practice of Usury, built out of the parallelism of “With usura”:

With usura hath no man a house of good stone

each block cut smooth and well fitting

that design might cover their face,

with usura

hath no man a painted paradise on his church wall.

Usura does not only prevent fine art, but all the useful arts too: “Stonecutter is kept from his stone / weaver is kept from his loom.”

With usura, we cannot find sturdy houses that will last the ages, nor any paintings inside their walls. Therefore with usury “no man can find site for his dwelling”; he is metaphysically homeless. Paintings are the homely hosts of “harpes et luz,” 15th century French for harps and lutes,18 from out of which “virgin receiveth message / and halo projects from incision.”

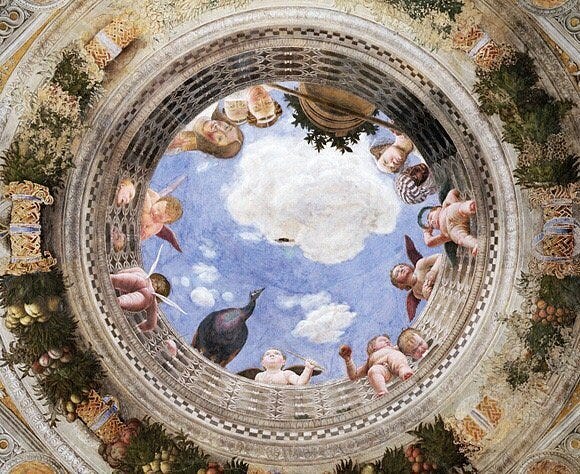

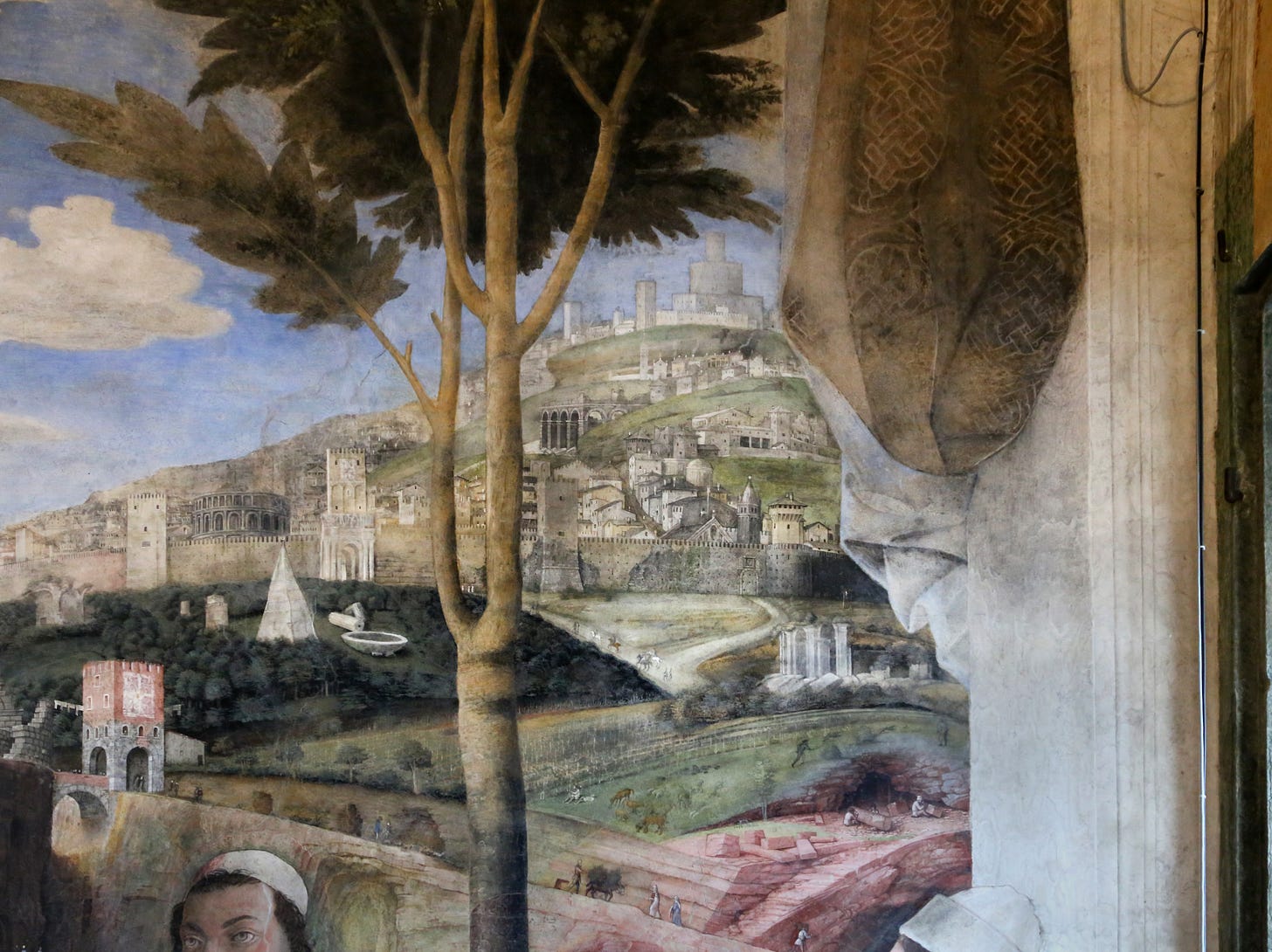

He provides an example: “with usura / seeth no man Gonzaga his heirs and his concubines / no picture is made to endure nor to live with / but it is made to sell and sell quickly.” The Gonzaga were a family from Mantua. The artist Andreas Mantegna, in their employ, leapt the progress of painting forward several generations. He was a neo-pagan who incorporated his vast classical learning into his frescoes, breaking out of the standard painter’s repertoire of Madonnas and Christs. Most dramatic is his Camera della Spoglia, a room featuring frescoed full-body portraits of the Gonzaga family, in ducal clothes like Roman majesty, standing beside the pope and the holy roman emperor.

Above them is a portal of pure grace: cherubim and a peacock.

But behind them lies the real art. Andrew Graham-Dixon points us to the castles in the background behind their heads: ornate palaces and Greek statues bask in the sunlight at the cerulean mount, while workers toil beneath them, carrying materials from the mines to furnish these luxuries. In the valley below the promontory is the punishment that awaits should these slaves refuse their labor: gallows and gibbets.

“Society is founded upon crime, and a social order clothes and hides its dark deeds and dirty secrets in opulence,” Graham-Dixon interprets, “where there’s wealth, there’s been violence, repression.” He carries this analysis over to Mantegna’s monumental series on Caesar’s triumph, where the dictator perpetuo carts back into Rome the spoils of war, surrounded by a procession of happy warriors.

Pound is comfortable with this reality. He bestrides a middle ground between Machiavelli and Lynch, where the pursuit of the good requires some violence and rapine in order to stave off the greater evil of usury, the sickness unto mediocrity and enslavement by bankers, whose financial tricks make it impossible to produce great art—art being the portal through which the halos of light enter our world.

Pound, at the end of The Cantos, seems to lament his efforts, writing:

I have tried to write Paradise

Do not move

Let the wind speak

That is paradise.

Let the Gods forgive what I

have made

Let those I love try to forgive

what I have made.

While Pound’s concluding motto is “to be men not destroyers,” the task of building requires Love, which cannot be reached through lovelessness. We cannot will ourselves into power; power comes to and stays with those who scarcely want it.

Pound represents one way to respond to the Holderlin revelation of nature plus supernature, where we accept the violence of the world while opposing “usura.” We succumb to our fallen nature and use it to bully society into allowing for the production of proper poetry. This can serve as a working definition of fascism.

Total Bliss

The alternative way of reading the Hölderlin revelation is Cooper, who accepts the infinite unfulfillable ethical demand of the situation-become-universal and shows responsibility to it. As I have argued elsewhere, Renaissance art was born from the mystic morality of Saint Francis, not the revival of Roman kampf. The fixation on power stems from an anxiety with our existential lot.

Rather than get furious with the evil to the point where our days are spent ranting at our lack of patronage, foaming with greed and the masochistic fantasy of being snubbed of the illusory golden ticket, Lynch says we have to cultivate luck through Transcendental Meditation:

I’m telling you, Fate drives the boat. We human beings, I don’t know what we do really, we don’t do much of anything: we’re guided by Fate, and luck… and it keeps us sometimes out of bad trouble or gets us into bad trouble… I’ve been so lucky in my life, just so lucky, I can’t tell you. And it all adds up to the greatest luck which is getting that mantra and learning Transcendental Meditation. That’s the luck, that’s the thing that will take away.

Lynch was a firm believer in the afterlife. “You know about death. But it’s just a change. Not an end. Hawk, it’s time,” the Log Lady says on her last phone call.

At the end of the meditation podcast, Lynch discusses all the religious beliefs as well as the atheistic and agnostic positions, and resolves that no one knows the answer until death comes. “But there’s really only one truth,” he adds, “and someday, somehow it’ll all get sorted out, and everyone will be happy. But right now it’s like, y’know… a jungle out there.”

Similarly, Frost writes at the end of The Final Dossier:

Or can the simple, impossible act of persisting to look at what’s in front of us finally pierce the blackness and reward us with a glimpse of something eternal beyond? Is that “heaven”? How do we manage it? The only answer I can console myself with is this: What if the truth lies just beyond the limits of our fear, and the only way to reach it is to never look away? What if that’s why we must keep going, why we can never quit trying to overcome it in every moment we’re alive? (116)

The true end or “Paradiso” of the Twin Peaks universe, in my reading, is the end of Fire Walk With Me, when Cooper presents Laura with her guardian angel. She weeps in happiness. Next to her is a blue lamp of the planet Saturn, or Chronos. Laura clutches her breast, mirroring the Capitoline Venus beside her, while the angel clasps her hands in prayer.

“The Invention of an Epidemic” – February 26, 2020. https://www.asc.uw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Giorgio-Agamben-Invention-of-an-Epidemic.pdf. Original: https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-l-invenzione-di-un-epidemia.

What is Political Philosophy, 41.

24-25.

55.

Critchley: “Of course, such an ethical demand is profoundly paradoxical: can a human being achieve divine perfection? Obviously not. Yet, it is precisely the paradoxical character of the demand that interests Logstrup for it emphasizes its radicality” (53). “Logstrup’s work can be seen as a questioning of the ethics of autonomy which is obviously dominant in Kant and his epigones and arguably still latent in Badiou’s account of the co-originality of subject and event. What is announced in Logstup is the possibility of an ethics of heteronomy, or better, a conception of ethical experience which no longer orbits around the auto-affection of the subject, but is articulated through the hetero-affectivity of an unfulfillable, one-sided and radical demand” (56).

40.

Who is Judy? We are first told about her when Phillip Jeffries (David Bowie) teleports to Gordon Cole’s office in FWWM/MP. First, he says he won’t be talking about Judy; then, changing his mind, he says “Judy’s positive about this … I’ve been to one of their meetings, it was above a convenience store. It was a dream; we lived inside a dream.” According to The Final Dossier, an ancient Sumerian demonic entity known as “Joudy” was said to wander the earth, feasting on human flesh and souls, nourished by suffering. Joudy was the female counterpart, “Ba’al” or Beelzebub was the male (BOB?). If the two forms were ever to unite it would bring about the end of the world—possibly what the magicians in the desert were trying to do (see below). It adds that the name “Joudy” was carved by knife into the wall of Phillip Jeffries’ hotel room in Buenos Aires, the same one we see in Missing Pieces when he teleports away from Gordon Cole’s office. The most we are told about Judy in the show when Gordon Cole in Episode 17 says: “Before he disappeared, Major Briggs shared with me and Cooper his discovery of an entity—an extreme negative force, called in olden times, “Jowday.” Over time, it’s become, “Judy.”” Briggs was shown reading from The Book of Revelation in The Missing Pieces on the night of Laura’s death.

Frost really goes off in The Secret History of Twin Peaks. There, we are informed that a man named Jack Parsons teamed up with L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, to carry out rituals that would trigger the end of the world, which the FBI believes were related to magic and rockets (sounds like Gravity’s Rainbow). Jack learned about the rituals through the writings of theosophist Aleister Crowley. Their first ritual, at what the Native Americans called “Devil’s Gate” in Pasadena, was supposed to summon “the goddess Babalon”; the second ritual was supposed to summon the “moonchild,” another Crowleyite term. According to a footnote, in his novel Moonchild Crowley spoke about a battle between two lodges led by black and white magicians over an unborn child possibly representing the Antichrist, a battle Crowley attempted to reenact in ritual. (Another footnote says Crowley based his entire anti-Christian religion on Thelema, Greek for “will” or “intention,” an idea stolen from Rabelais in what was intended to be satire.)

They chose to attempt the rituals near White Sands in the area known as Jornada del Muerto, “the journey of the dead.” Parsons says the desert, combined with the fact that the bomb was detonated there, made it the perfect place to “create an elixir that will call forth … call them what you will … messengers of the gods” and commence “The Working of Babalon.” Later, when the detective asks the suspect why Parsons wanted to summon “the goddess Babalon” in what sounded like an attempt to end the world, the man uneasily says he doesn’t know what Jack was after “but that it took two people to enact the ritual.”

When they performed the ritual in White Sands, the UFO crash in nearby Roswell occurred. The implication seems to be that this was the source of the Woodsmen in Episode 8 who wander into town, murder the AM radio host, and speak their hypnotic Revelation-esque poem into the microphone. Once the Woodsmen paralyze the city, the mutated moth that entered the world following the nuclear explosion is able to climb through a little girl’s window and enter her mouth. This was probably Sarah Palmer, Laura’s mother, as a little girl (Mark Frost confirms that Sarah was raised in New Mexico in The Final Dossier).

In the bizarre scene of the lady in the car with the sick girl, she tells Bobby they are late to dinner with the girl’s uncle who they haven’t seen in in a very long time. Perhaps this is BOB, who in the form of Mr. C will be returning to the town to meet Judy and unite with her. The combination of the positive extraction of pain and suffering with the extreme negative force.

The dwarf, called “The Man from Another Place” or “The Arm,” at first seems to be a neutral character, but is in fact in charge of BOB. In Fire Walk With Me and The Missing Pieces, the dwarf and BOB are seen together above the Convenience Store surrounded by bearded men (Woodsmen?), stirring and eating from a pot of “garmonbozia.” “Intercourse between two worlds,” the dwarf says, “this is a Formica table…” “I am the fury of my own momentum!” BOB yells back. The dwarf responds: “…with this ring I thee wed.” The dwarf seems to be saying that he is the ringleader of the enterprise, and that BOB, who wants to claim independence, is still his indentured servant in murderous evil. (The ringleader of the corporate conspiracy in Mulholland Dr. was also the dwarf.)

Matthew 4:8-10. Douay-Rheims translation.

Faust II, Act V, “Mountain Gorges,” lines 11,936-11,937.

This sounds like it works with Deleuze’s ethics along the lines of Spinoza’s Conatus, but it’s not, because it also has an intense sense of the Ego derived from Christian-mystic tradition, which is at odds with Deleuze’s project (see his essay “From Christ to the Bourgeoisie”). By contrast, Lynch’s thinking proceeds along the same lines as Heidegger-Levinas-Derrida-Critchley, where phenomenology makes room for a sense of self that is not conflated with Descartes’ subject because it has an innate sense of external being (ecstatic temporality) which is also not conflated with Descartes’ object(s)/bodies.

1 John 2:15-17. Douay-Rheims translation.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “Of the Three Evil Things.”

43.

55.

A quote from the ballad “Testament” by François Villon.

floored by this writing

an astonishing range of expression

keep ripping out the connective tissue

well done