Chapter 8: Nietzsche

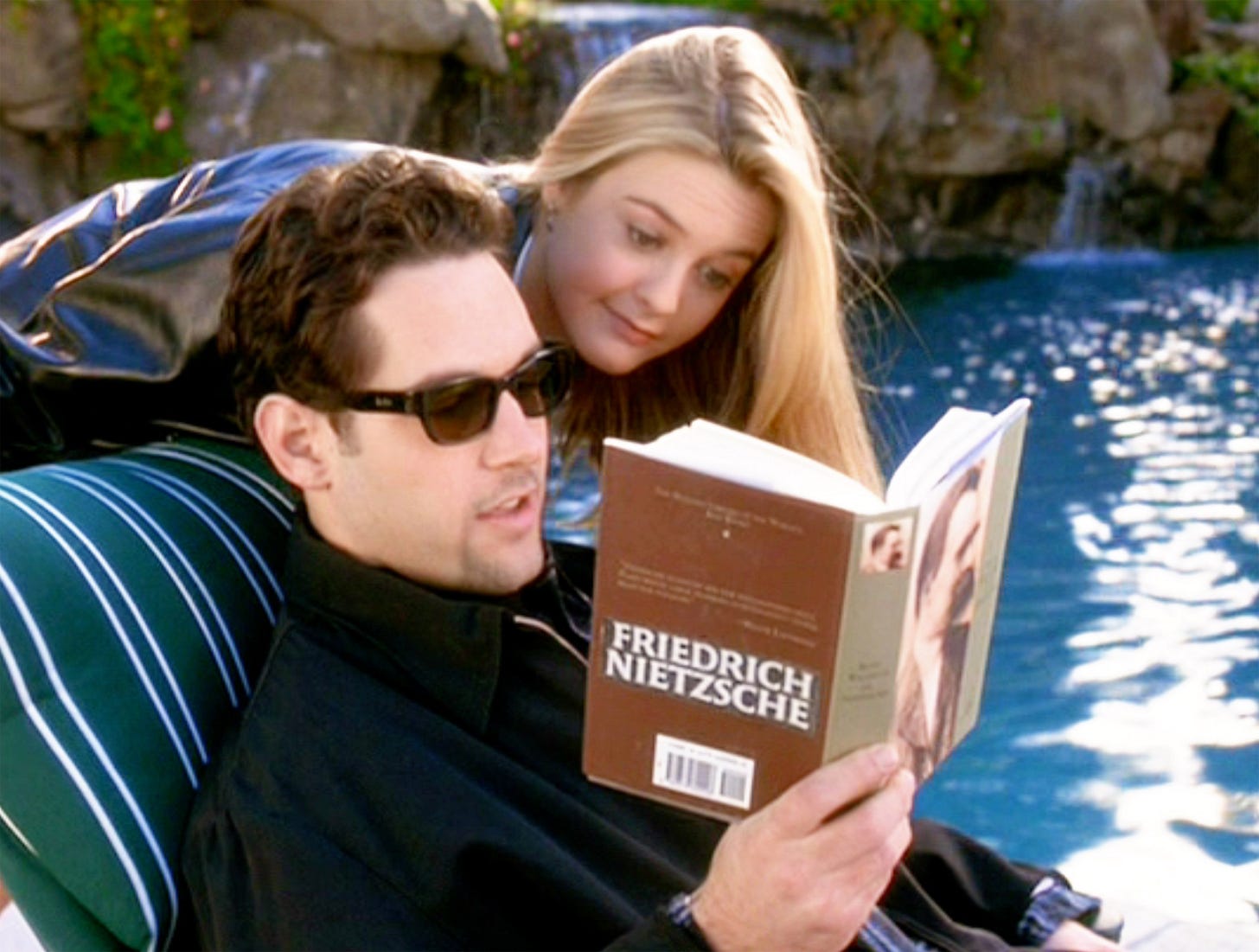

Before I let the story take off, there is one more character I need to introduce: Nietzsche.

Someone you always think you’ve surpassed, but when you return you find him once again so far beyond you. The torturous laughing satyr who courts the young and trips up the old and “wise.” His writings wrapped into one body of work everything I had experienced: the death of God, the stepping over nihilism into a glorious lightness, art as life’s justification, the rejection of societal wardens, eternity as the immortalization of great deeds. And he did all this through a discourse about nature and history alone, without recourse to any supernatural or metaphysical bullshit.

After reading him I no longer cared about the gossip police and was pushing against all rules: taking psychedelics, saying whatever I wanted, asking girls out, applying to an art school in Manhattan and rejecting all “responsible” objectors, replacing my musical rotation with Kanye West and The Doors, professing my love to a teacher and almost getting expelled (a story for another day).

I don’t know how I found Nietzsche; it was more he that found me, by being referenced through one hundred different avenues: Gaahl, Varg, my father, the teacher I loved, quotes in the aether, shitposts on the internet, CLT.

He found Alexandre and me at the same time and became our older, oracular friend, who we sometimes mocked but revered, and who mocked us back, always daring us to push further, to act more erratically. To Alexandre he bestowed an artillery of rhetoric to smash democracy as well as a supply of marble to build a new hierarchy. To me he bestowed keys to the shackles of pale Truth and spiritual cocaine whose high was an exuberant lust for the future.

We hatched a plan: I would come up to Québec City for a week after getting my license (18-year-olds can buy alcohol in Canada) and then he’d come down to America for a road trip. He told me I had to meet Henri, his “only equal,” and Natacha, his lovely girlfriend who would travel with us.

I told Alexandre once that I still couldn’t decide between pursuing literature or something “practical.” He replied:

3/2, 2:40pm

Grey is, young friend, all theory:

And green of life the golden tree.

Let but this ancient proverb be your rule,

My cousin follow still, the wily snake,

And with your likeness to the gods, poor fool,

Ere long be sure your poor sick heart will quake!

this is your answer

And he in turn said he couldn’t handle the future, that his stepfather was pressuring him to become an engineer. I answered him:

4/21, 11:36 PM

But your fate has already been decided. You will go on the road, achieve that Beat communion with everyone you’re looking for, travel America, and choose the life of an artist.

“Did you ever say Yes to one joy? O my friends, then you said Yes to all woe as well. All things are chained and entwined together, all things are in love; if ever you wanted one moment twice, if ever you said: ‘You please me, happiness, instant, moment!’ then you wanted everything to return! you wanted everything anew, everything eternal, everything chained, entwined together, everything in love, O that is how you loved the world, you everlasting men, loved it eternally and for all time: and you say even to woe: ‘Go, but return!’ For all joy wants – eternity!”

He objected, saying, what about those who say Zarathustra is just the mad writings of a man who’d gone insane from syphilis? I implored him to reread it, stressing that from the raw diamond mines of Zarathustra we’d cut our teeth razor sharp, with which we could say and mean things like:

“All things themselves dance for such as think as we: they come and offer their hand and laugh and flee—and return. Everything goes, everything returns; the wheel of existence rolls forever.”

And: “To redeem the past of mankind and to transform every “It was” until the will says: “But I willed it thus! So shall I will it.””

And: “to the discerning man all the instincts are holy.”

And: “He whose fathers passed their time with women, strong wine, and roast pork, what would it be if he demanded chastity of himself?”

And: “The best belongs to me and mine; and if we are not given it, we take it: the best food, the purest sky, the most robust thoughts, and the fairest women!”

And: “He possesses heart who has fear but masters fear: who sees the abyss, but sees it with pride.”

And: “But now this God has died. And let us not be equal before the mob. You Higher Men, depart from the marketplace!”

And: “Willing liberates: for willing is creating: thus I teach. And you should learn only for creating!”

And: “Lead, as I do, the flown-away virtue back to the earth – yes, back to body and life: that it may give the earth its meaning, a human meaning! May the value of all things be fixed anew by you. You solitaries of today, you who have seceded from society, you shall one day be a people: from you, who have chosen out yourselves, shall a chosen people spring – and from this chosen people, the Superman.”

The ferry’s horn blew. The Hudson all blue-gray with bubbles and trash bumped to the bow of the ferry, rolling and unrolling foam again and again. I boarded, like Marlow’s embarking for the Congo, or Ishmael’s restless hat-smacking leading him to Nantucket, or Sal Paradise heading to Denver for the first time. It did its turnaround and sailed forward to Manhattan which was silhouetted in the early morning white. I buttoned my jacket and stood up, leaning against the railing. Young girls and their mothers sat in the corner stressing about buses; a businessman tapped his foot, looking at his watch. I calmly turned away and looked at the city; in my bag, my passport, clothes, and Zarathustra with Alexandre’s address scribbled on the last page.

We docked; up the walkway to the glass hall, then out to shuttle buses and the people all bickering and shoving. A man rushed past me into my targeted cab. I was in no rush. I waited ten minutes to see a cabbie curling his fingers into a crook. I rode the shepherd’s cab up to Port Authority where I collided with homeless scammers offering false directions for a donation. Avoiding these guides, I found the basement and the Montreal greyhound already boarding. I handed the man my pass and sat at the far back window.

The bus left Manhattan and drove up to Albany, then took I-87 into the mountains, fully dressed in fir trees, so wide and thick in number that they blended into each other as one big rug that ran down the sides and back up other hills, behind which I could briefly see entire woods untouched until a new mountain would block my vision. Burning, swelling in its grand appearance, the morning sun came rising, its fingers dawning over the joyous and still virgin earth. North into more woods, lakes popping up for seconds and disappearing, flying without stop, up out of New Jersey, out of America, into something else, to greet the festive mountain people of frozen France.

After passing through customs the bus drove a little further into the Montreal station, a big hollow glowing white concrete atrium. Now all the signs were in French, with English translations occasionally provided underneath in smaller font—I was later told this was due to a law passed by the Québec government against their Anglo overseers in Ontario. I took a cab to the train station, passing the old Québécois women smoking Virginia Slims, the college students, the working professionals, the signs of bars and the monuments in parks. I was far removed from high school now. I paid the cab driver in money just converted into Canadian coins, before the days of Uber or one-tap credit cards.

I boarded the train and opened Zarathustra, which was almost over. Its conclusions, its soaring crescendos mashed with the flying-by scenery outside of my window, scenery of new lands, fresh starts, good spirits, all-together scenes of cheerful moods and signs of deep joy to come.