See the child. He is pale and thin, he wears a thin and ragged zip up hoodie. He scrobbles last.fm tracks. Outside lie dark turned astroturf with rags of snow and darker woods beyond: “there are still a few animals left out in the yard, but it’s getting harder to describe sailors to the underfed.” His folk are known for menders of animals and nursery schoolteachers but in truth his father has been an MRI technician. He lies in drink, he quotes from historians whose names are now lost. The boy crouches by the den rocking chair and watches him.

My mother and father had me when they were very young. I was born on the cusp of the 2000s. It is hard to explain what life was like in the early twenty-first century; it was as if the past had entirely vanished from the minds of men. When it would rear its head, it would provoke a joke or two before vanishing back into the abyss from whence it came. Everything was coated in a veneer of neon-colored plastic: George W. Bush was in office, and, as the Québécois would later inform me, Americans always take on the personality of their president. On my block, a typical north Jersey neighborhood, dozens of kids rode their bikes on their back pegs with drawstring bags talking about terrorists, the conspiracist Star Wars prequels, and video games set in the Middle East. I was one of them, and was otherwise destined to become like their parents: landscapers and firemen, janitors and teachers.

But my father, a young and angry man born to cold, harsh Irish immigrants, was an outsider. His father was the son of a farmer from the rugged northern county of Donegal, lacking electricity and heat. His mother, my great-grandmother, died when he was in third grade, and he was thus forced to become a man and take care of his siblings and his family farm. When he was twenty-five, a local elderly farmer had more flax than he could manage, so he held a contest to see who could harvest the most. My grandpa participated against two other men from the village and won. Taking the prize money, he bought a boat ticket and sailed to New York, where he immediately began working as a boiler serviceman for Public Service Electric & Gas. He made so much money the first month he was here that he mailed the same $20 bill his father gave him back to Ireland.

My father in turn was the youngest of five, an afterthought. When he was just a child, my grandfather would bring my father along with him to his job sites, forcing him to help install boilers in the freezing cold, calling him stupid and worthless. Yet all this time he was reinforcing in him the perspective of a farmer from a rural part of the Old World, with a distrust for commercials and a loathing of bankers, which he cherished as the real outlook as opposed to the false one of the modern Americans he grew up around.

But he was being raised in America, to become an American. Through his schooling he came to have an appreciation for the nation’s history, almost as a form of rebellion against the purely practical mind of his father. He told me his first revelatory moment was when he had to write a book report on Lafayette and discovered that during the American Revolutionary War the famous revolutionary had traveled down the road he grew up on. This locked him into study for life, and he maintained it through his teenage years of hockey playing and drinking in the woods. My grandfather also made him learn the bagpipes, fostering in him a love for music. So in the evenings he would go to the garage to build furniture, repair his truck, read books on the French and Indian War or, later, on astronomy and physics, and practice his bagpipes. I remember once, during a massive storm, he was outside heaving a Scottish marching tune as a lightning bolt struck a giant tree in our yard sending bark and branches flying, yet he played through it like a maniac druid.

Once, when I was eight years old, I was sitting with my father watching the chiminea burn on our backyard patio. I must’ve been asking him questions about heaven or something of that nature, and he replied that he did not believe in God. I looked into the flames and saw the faces of the priests at our local parish burning. From that point on, while I still attended catechism classes at my Italian mother’s fierce insistence, I knew in the back of my mind that faith was an option; and gradually my beliefs fell away as I learned more about the natural world, guided by my father’s knowledge.

From such an early age I conceived of human existence as a question mark—something we could do with what we wished. My father also gave me a sense of admiration for greatness in human beings—however rare. He believed that humans were for the most part worthless, all of them flawed, and our overall presence in the universe was like that of a cancer cell, destined to use up the earth’s resources and kill off the rest of the animal kingdom in the process. Yet he pointed to some deeds—the frontier days of America, the Enlightenment, and, later, the ways of the ancient Celtic and Norse pagans—as noble.

After that my father left. Imparting me with the absolute freedom of beholding Nature without theology, and bestowing the ability, the passion, to search out what is highest in humanity, I went on, adrift amid the currents of life, unfettered by many traps of control which snare so many, bristling to discover the few who could unveil the overpass to nobility.

Torn from all anchors, I craved truth like a parched desert wanderer. I sought out science, went to its bottom, and found nothing but tears and scorn. I began by reading a lot about the Enlightenment—my father left behind a copy of Voltaire’s Candide, which he said was his favorite book; I loved Voltaire’s cheerful mockery of dogma and his refusal to add blush to the true, brutal face of the world. By way of Hitchens I read Thomas Paine’s complete works, and some Jefferson—all this was good, but the watchmaker deism in it felt hollow. I needed something more, up-to-date, that would explain what happened before the Big Bang, and how we evolved out of the inorganic. So I read my father’s books on physics he left behind only to become overwhelmed by the meaningless picture of the world brought on by the plainness of matter. Material knowledge, I very gradually and painfully learned, was the path of despair. The view of the cosmos given by astronomy, for example, vast beyond comprehension with our place in it so absurdly small, can easily push a teenager already weary of their future prospects to soften the consequences of suicide in their mind. I have grown to pity anyone encased in mathematics and raw facts, unable to appreciate the inherent mysteriousness of truth.

The first step out of nihilism was to hear the inner essence of the claim of Darwin: that we are animals, and therefore the truth is what pleases us, not what voyeuristically grants us a vantage point into the workshop of God. Not the pleasure of the senses, but spiritual pleasure, the spiritualization of sense, in the vein of Goethe, who asked: “For what end is served by all the expenditure of suns and planets and moons, of stars and Milky Ways, of comets and nebula, of worlds evolving and passing away, if at last a happy man does not involuntarily rejoice in his existence?” Goethe, despite his pomp, deserves to be quoted here: he was the perfect man to say this, as he dedicated his life to the study of nature only to celebrate it in exuberant poetry.

Music was the sole consolation away from all the dreary shit of those middle-years, as it is for so many teenagers, astride the beginning and end of high school. But for me music was specifically a way to repair the fissure torn by science and the idea of laboring away in a purposeless world. In music I was free to yearn for a greater life; to find joy away from family discord; to feel the grandeur of Nature as an antidote to the miniscule horizon permitted through the mental gates of provincial Bergen County, not from the study of Nature’s mechanics but from its impressions on the souls of great artists, and thereby have a share in the community of celestial powers which Emerson calls “that gleam of light which flashes across the mind from within.” According to Emerson, a true Adam of America, a writer my father read with some interest on his college camping trips, our first “latent conviction” should be trusted, for it will inexorably become “the universal sense.” In the deepest core of the Individual lies the gold of the cosmos; the external blabber means nothing. But too often we exile it out of fear, only for us to meet it again in the works of the greats. The community of Genius is nothing but the collection of fresh thoughts untrammeled by second-guessing society’s censoring iron chains, which aim to shackle us in ideas devoid of power. In music the latent convictions of man run free, bypassing even language, which is its own kind of prison; passions pure, pressed into sounds formed of ivory and string, reach into the air like golden tendrils and bloom into a thousand colors, passing off seeds to grow new continents. How much more sublime this was than science, and warmer: a discourse made not for numbers, for machines, but for men, existing for no other reason than to make the world more blessed.

I wasn’t always like this: in the summers of elementary and middle school I built tree forts with friends, played Xbox, and rode bikes to Burger King where we hung out with the rest of the kids in my grade. I went to school dances and listened to all the pop and hip-hop, downloading songs on LimeWire. But the revolutions in my inner life sent me on a course of artistic inquiry that has never ended.

In early high school I lived in the hoary lands of Scandinavian and Celtic folk metal, beginning there for some reason or another. Gradually I found my way to the scorched earth of black metal, finding first Gaahl, the singer of Gorgoroth, whose VICE documentary was a gateway for me into the world of philosophy. He quoted Nietzsche, a figure I had heard of but was confused by, with abandon, tying it into a satanic individualism and self-responsibility so characteristic of the modern Nordic people, using it as a cudgel to bash over the heads of the out-of-shape VICE journalists who could not keep up with him on the long mountain hike. He tried to take them to its peak—they couldn’t make it. He told them how he grew up on that land, his ancestors’ land, and how he went to a small village school with one other student, and how that student, at the end of his education, committed suicide. After telling one of the journalists that he is not asking the right questions and is focusing on what he is being told, the journalist asks him to “guide” him—Gaahl looks away in disappointment for three minutes, and the documentary ends.

Alone and towering over the world from his mountaintop, Gaahl represented for me the perfect freedom of the artist, who combined the total freedom of thought with the creative expression of deep feeling. This was the type of life I wanted to have. I began to grow apart from the popular kids at school, with whom I used to party, play beer pong, pace around in parking lots as we waited for seniors to bring back the cases of beer or Four Lokos (always overcharging us of course) from a seedy liquor store in Paterson that sold to minors… I eventually found it boring and hated the way they took hard-earned money from their parents to buy alcohol. Fury with the given world came over me. I remember discussing our futures once, and realized they had no plan, intending to drink cheap beer and live in town forever. Or, which may have been worse, they obsessed over sports and extra-curriculars and a host of other anxieties to get into the right colleges, so they could make money for overweight globalists—all forms of pressure and repression placed on them by teachers and the principal. I replaced those friends with misfits, stoners and musicians. I would walk home alone, listening to these bands, in drizzle and in sleet, across the whole of town to my home on the border of it, tucked away behind an obscure park, nestling itself quietly under colossal trees. There, often alone for evenings and weekends, I would explore the universe of music from my computer, seeking out ever more exotic sounds.

I was eventually led to Varg Vikernes, one of the originators of Norwegian black metal, operating in the 1990s and having largely disappeared from the music scene since. I had previously listened to a lot of “technical” metal recommended to me by my musician friends, who praised it sheerly for virtuosity and complexity: djent bands, the god among them Meshuggah, or “epic” cringe bands like Blind Guardian. Or it was thrash metal, like Slayer and Megadeth, who were loved simply because they were “intense” with overcharged guitar shredding, or death metal, with double bass pedal “blast beats” that would unwind into dramatic drops before launching again into chanting raves. These artists were always trying to outdo each other with cleaner production and more bombastic presentation, endeavoring to impress and wow the internet masses. Varg, with his one-man band Burzum, flipped all this on its head. He had some precedents like Bathory, or contemporaries like Mayhem and Darkthrone, but these had nothing on what he created: slow, repetitive, simple tracks, using the worst recording equipment he could find (there was a story about how he tossed aside his cheap microphone for an inferior helicopter headset because it recorded a harsher sound), screeching like a demon over hi-hats and a melancholic synthesizer. And yet he achieved infinitely more than them. My friends hated it, but I was engrossed. I had never really encountered art like it before, music arranged not to express clear thoughts through lyrics, in the case of rock or folk, nor to impress the listener with technical skill, nor with a clear beginning middle and end as in pop, but rather to cultivate an ongoing atmosphere out of basic parts.

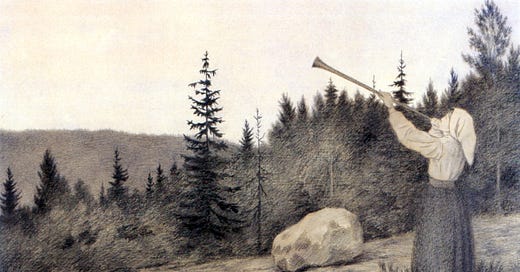

With album covers taken from old Norwegian sketch artists or from grainy photographs, he would plaster his band name BURZUM across it in Gothic font. His first, self-titled, was guttural and gloomy; he said once that he had said everything he wanted to say in his very first song, “Feeble Screams from Forests Unknown,” in which a narrator describes a soul hovering above a freezing lake; further into the forest lay theories to lift the locks on the gates of primeval Nordic religion, without luck; and ending with the lines: “As years pass by / The aura drops / As less and less / Feelings touch / Stupidity has won too much / The hopeless soul keeps mating.” Modernity as stupidity. Everything thenceafter in his discography is elaboration and concealment. By the album Filosofem he reached what I view as his peak, in which scorching blazing guitar riffs course under and over the relentless fury of fuzzy cymbals clashing, with him belting out seething volcanic blasts of wrath and rage, screaming about the death of Christianity and the hopeful return of the pagan gods. It dissolves into a 25-minute ambient electronic piece, “Rundgang um die transzendentale Säule der Singularität” (“Circumambulation of the Transcendental Columns of Singularity”), which softly broods like that freezing soul, floating above the meaningless ruins we live in. This made Gorgoroth, and certainly everything else I used to listen to, seem as effeminate and histrionic as Disney and Broadway—here was everything they were trying to express in far fewer words, much less cover art, far more feeling and truth, an incalculably greater amount of honesty. Nothing sees further than honesty, nothing is more capable of reaching far-flung discoveries than the spiritual mileage unleashed by moral and intellectual probity—which inevitably leads the mind to overturn pieties and introduce ideas the press would call dangerous.

In the late 90s Varg went on a crime spree. When the first McDonald’s opened in the country, he rode bikes down with his anti-American friends to fire BBs through its windows in rebellion to globalization. Then he started burning down numerous churches in the name of Odin, attacking what he saw as an alien, Semitic religion imposed on the Nordic people. Finally he murdered Euronymous, a communist-satanist bandmate who was plotting to kill him. Varg claims Euronymous tried to stab him first, so he knocked him to the floor in self-defense. But Euronymous’ corpse was found with 23 stab wounds—Varg claims a lamp fell over, but we can imagine what really befell the beserker. The authorities ended up connecting the man who committed the recent murder to the church burnings (which wasn’t too difficult, as he made a photograph of one of their charred remains his second album cover). He went to prison, but only for 21 years due to Norway’s lax criminal punishments. While serving time he read copiously about ancient Europe and shared his findings in blogs, broadcasting to the world his fervent contempt for the modern world, democracy, and racial tolerance. I read them with relish, never having heard such thinking prior: the better lives that women had under tradition, the way that capitalism and socialism combined forces to destroy the natural world, the way that Christianity led to the desacralization of nature and directly caused the nihilism of our age, the way that multiculturalism poisoned the tree of European heritage. This was everything I was looking for, a fusion of my prior scientific atheism with the paganism I had grown fascinated with, complete with my father’s misanthropy. While I was eventually distracted by other things, looking back this dissolution of the liberal conscience clearly served as a steppingstone to my reactionary conversion and made ingesting those ideas much easier.

I would browse metal pages on Reddit, a website which I hated but used from ignorance of an alternative. From there I found memes of Varg jesting about his flurry of crimes and his racism. I learned that the memes were from 4chan, a website I had used a few times in middle school. 4chan to my mind was a lark, a place for people to shitpost with the most offensive flair, totally anonymous and deranged. It was known as the utter cesspit of the internet. I had no idea they had a music board, /mu/, or any other boards beside the main one, /b/, which was then chiefly known for producing the hacker-activist group Anonymous and pulling off several infamous stunts to troll the media.

So I started to browse /mu/. I soon learned that besides Burzum, metal wasn’t respected there; “meal is for kids,” the catchphrase went. They preferred indie, with a memetic obsession for In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Neutral Milk Hotel, a Louisiana “fuzz-folk” band which paired strange instruments with stranger lyrics about childhood and the singer’s more-than-Platonic love for Anne Frank. I liked it, grew to love it even, but never fully fell in love with the acoustic indie genre, finding it derivative outside a couple outliers and ultimately all-too wispy in character, enfeebled and pathetic.

In hindsight, it was in the album-ranking threads that the origin of my concern with “taste” began. They are therefore the key to understanding everything to come. It was stupid teenager stuff, but we all know how teenagers find these niche groups that mean so much at the time. You would share your favorite 10, 25, or 50 albums, which you would plug into an image generator that would produce a chart of all the album covers, and you’d post it into the thread hoping for a compliment and some recommendations of similar music. Instead, they would reply that you had shit taste, or no originality, or that you were a “[microgenre]-fag,” and so on. “-fag” was the common suffix on the board: everyone was a gigantic “faggot,” everyone was constantly shitting on everyone and telling them to develop better taste. This was my first exposure to the very concept of “taste.” I had older cousins, who had shown me what “good music” was in middle school, and my father would insult music here and there, but I never had conversations with this degree of concern for aesthetics, obscurity, experimentation, and sophistication. However immature the discussions were, they were formative at least in the glimpsing of the notion that there could be better and worse works of art determined along purely aesthetic lines, according to stylistic choices that could not even be pinned down to formal complexity or to time period or to the ideas expressed, but something wholly other, at present totally unnameable.

Posters who used a tripcode, a line of generated numbers and letters produced by choosing to use a username and password in the post field, were called “tripfags.” They were the princes and, more rarely, princesses of the website: even though the masses of anonymous users derided them for attention-whoring they nevertheless routinely gave them the attention they ordered, gossiping about their lives and turning their personalities into legends.

One among them, “CLT,” was the king of the /mu/tants. At that time all I knew about him was that he had very good music to recommend, and that he would pop into threads to insult everyone in sight using an aloof yet intricately well-reasoned and well-worded posting style. He would send anons into absolute rages, and seemingly gain energy from the hate he would receive. The greater number of posters he would infuriate, the greater would be his replies; and yet he also had this politeness about him to those sincerely looking for help which won me to his side. The most influential contribution he made to the discourse of the board, and eventually to the entire website and beyond, was the introduction of the “pleb/patrician” dichotomy, becoming the new judgment hierarchy of posters’ taste. No longer could you be free to hide behind subjectivity or to being a “fan” of this or that genre: according to his dichotomy, your preferred artists, down to the specific album or era of their work, or even to the song, made you a patrician or a plebeian, regardless of genre, and this judgment-making ability carried over into any genre you commented on, meaning that you were either a member of the elect across all styles or a master in none. I have a suspicion that this dichotomy seeped into all areas of life and was responsible for the hierarchist reactionary politics that engulphed the counterculture in the late 2010s, but we will get to that in due time.

It became my obsession to improve my taste, which amounted to listening to more music. I downloaded gigabytes upon gigabytes of mp3 and FLAC files, getting special software to listen to the latter since iTunes couldn’t play it. I would look through other users’ charts and track down anything I could find on various pirate websites. I used the guides created by critics in hopes to discover what exactly it was that set apart good music from bad. I knew, at least, from Varg that it could not lie in what was most complex, and from CLT that poor music was certainly poor, which was easier to establish. It was in the critical observation of what made bad music bad that I formed my first footing regarding questions of aesthetics, which, as a form of judgment concerning good and bad, served as the baseline of later evaluations in politics, love, and friendship. Regardless of these philosophical niceties, it was simply good music, which permanently enriched my enjoyment of life—and also served as the portal out of my small neighborhood in New Jersey and into the vastness of the earth.

Love the writing. I didn’t realize how universal the experience with music online was for people born just before the turn of the century. I feel like I’ve had so many similar discussions like what you had growing up

tanks