It seemed like everything came to a head and began to unwind when DooblyDoomsday released his terrible book. It wasn’t the book itself that caused this, but what it represented, and what it revealed about the nature of the Right. I remember seeing it while I was browsing Twitter at work one day. Its title was Hades’ Hatred and the prologue was full of similarly dreadful alliteration: “decadent decay,” “soulless solitude,” and so on. We mocked it, and in turn were attacked for this mocking, and we attacked them back, but most significantly we could not do away with the truth that had been unearthed, that the entire reactionary worldview boiled down to a vulgar poetics, a grotesque mishandling of culture: now that it had finally been executed artistically, its hideous face was unmasked.

Harold Bloom caused an uproar in 2000 when he wrote an op-ed for The Wall Street Journal to deplore the bestselling Harry Potter series as being so full of unthinking tripe, painful bromides, and Mary Sues that it was essentially unreadable. “I think that’s not reading, because there is nothing there to be read: there’s just an endless string of cliches, I can’t believe that does anyone any good” he said on Charlie Rose later that year. “Rowling's mind is so governed by clichés and dead metaphors that she has no other style of writing” he wrote for the LA Times in 2003. If Bloom ever let up on Harry Potter, it was only to lament the general downfall of the literate mind into a swamp of nullified inhumanness. “Will they advance from Rowling to more difficult pleasures?” he asked the Journal’s audience. His implication was that the Potterites could never graduate from that universe, because addictive junk by nature can do nothing other than spoil the appetite for healthy food. The facts bear witness to his prediction, because to this day the millennials still rely on that series as their sole literary reference.

I don’t think Bloom was seeking publicity or self-promotion, nor can his comments be discarded as the ranting of an old crank. I believe him that he found something “horrifying” about the greediness with which the masses lapped up what he saw as a hackneyed, unchallenging product, akin to an ill-made table being sold on the market, only for the censors to call the carpenters inevitably aghast at the faulty design snobs. Even worse for him were the museless authors from “diverse” racial and sexual backgrounds being celebrated as great craftsmen despite the poverty of their literary creations, the faults of which were justified due to their “social utility.”

This was the exact spirit in which we mocked Doomsday’s book. It was inconceivably bad, which wouldn’t have made it noteworthy if it wasn’t for the many e-celebs that endorsed it and tried to pass it off as the big “literary event” of frogtwitter, precisely in the same vein as the trash identity books being trumpeted by academic critics due to their fulfillment of political demands. The book had ‘based’ intentions, which made it good, and we were suspected to be political subversives for not agreeing along.

As I said, these were the days before monetization, when Jack Dorsey was still in charge, and the “humanities” section of Twitter was confined to just a few thousand accounts, almost all of them drawn to the discourse due to far-right political beliefs. There weren’t any academics, at least not any that we interacted with; the statue accounts were meager, not yet rolling out paywalled content and being promoted by Elon Musk, and the left-wing fascination with Deleuze hadn’t begun, which introduced a lot of Gen Z teenagers to philosophy, so most of the left-wing accounts were either embarrassing student council types or “dirtbag left” anons who wrote in defense of mundane healthcare reform under what they thought were thick layers of irony and sarcasm. The rest of the website paid no attention to discussions of art and literature, or to the destiny of the right-wing movement, or to the state of modern men and women, or anything like the ubiquitous culture war sophistry we see today. Most of its major users were journalists and commentators from the major networks—they hadn’t yet fled Twitter en masse due to Musk’s purchase of the platform. The dominant topic was the news cycle, which at the time was solely focused on Democrats’ attempts to impeach Trump for the Russian collusion lie and Trump’s hourly jabs back at them.

So it was in the context of “saving the West” (or maybe letting the West fall so the online Right could take its place) that all conversations on art were directed. It’s not clear why literature became popular among this group. Perhaps it is always literature, literature above anything else, that becomes potent as a symbol of cultural renewal to groups that believe such a renewal must take place.

It makes sense that a radical overturning of utilitarian first principles was required for the rediscovery of literature. We had overturned these principles ourselves long ago, in our own way, but the reactionary way was certainly a viable path. Indeed, why would moderate or progressive people desire to recalibrate our answers to fundamental questions? What liberal would seriously doubt the overall benefits of political and religious freedom? What socialist would reject the bases of community as the source of mediocrity? But both freedom and community, and any other force that brought us suburbia, had to be attacked for art’s transformative character to shine forth again and for the function of the work of art to be freed from its relegation to entertainment or escapism.

This is what we had in common with the posters on “frogtwitter.” The similarities more or less ended there. This became obvious the more we tried to get past certain topics and onto art, but were ceaselessly pulled back into moral panic discourse because the other posters were convinced such issues were the very things a new art would have to address—things like, say, the alleged sexual chastity of past eras, or the inherent evil of America, modernity, the enlightenment, etc., or the need to restore the power of the Catholic Church and have its priests rule society.

Like a city, frogtwitter was a collection of “buildings,” some very tall and grand spires that had been worked on with care over a long period of time. And just like any city, it had neighborhoods. But this was a particularly Old School city, where the neighborhoods were like gangs, tribes with very different values, all in a coalition of agreement on basic grievances like all the other cities in the world being bad.

One neighborhood was ruled over by two NYU grads, one being a German Idealist obsessive and the other a Nabokovian littérateur. Its people were addicted to “hot takes” about the past, like “Rome never fell” or “Atlantis is real and its data was uploaded to create the Facebook servers, which Zuckerberg will use to milk us for energy.” They would work hard on .jpegs, extensive murals displaying their schizo visualizations of a dystopian or utopian future, or dig through old books and share screenshots of information that were supposed to blow everyone’s minds. Their defining trait was contrarianism, and lacked any core belief beyond that. But they were popular because their posts, podcasts, websites, and so on were clever, arcane, and of high quality compared to the lot of trash and whining of the general far-right user.

Another neighborhood was the Trad Caths. They wanted to return to the Middle Ages, and they hated pagan antiquity almost as much as they hated modernity. This was long before the Catholic/Orthodox revival picked up steam and became an institution-backed movement. This version was much more aggressive and fringe. While the institutional version of today attracts many pie-baking females eager to put men back under their apron, these fellows were savage, closet computer gamers fantasizing about the crusades. They hated sexuality with a fearsome passion, and ruthlessly dogpiled anyone they deemed to be “degenerate,” especially a right-wing e-celeb that slipped up and revealed something “unchristian” about their personal lives. They latched onto the beauty of cathedrals, posting pictures of them constantly, claiming that such artistic beauty was only possible through God. If anyone brought up the artworks of the Greeks or the moderns, they would cry pedophile like the Church never had a scandal.

Then there was a gang of bodybuilders who stressed the martial greatness of the ancient world and the weakness of modern man. They were like an offshoot of the pick-up-artist sphere, in which Andrew Tate was operating in before going viral. They fell under the stewardship of one of the main frogtwitter characters, a guy who posted like he was Conan the Barbarian but turned out to be a Romanian-Jewish academic from a well-to-do suburb of Boston. We will call him RAJ. He would reference Nietzsche, as did we. We esteemed him and other posters of his caliber to be hidden poets who would make “great companions,” to borrow a phrase from Whitman, in the years to come. There were other groups, like the anti-western Duginists, or the defeatist “blackpilled” ironybros, or the unreconstructed wignats left over from 2016. But this was the general landscape of the ethereal city, with nearly all its residents being completely anonymous.

The sphere was obscure, but there was evidence it was being observed by powerful figures in the Trump administration and in the private sector, which upped the ante of all the moves that occurred in it. If someone could pull off a great work, it was believed, they might be awarded with real world success, and more importantly for this crowd, power.

Our group was small and on the outskirts. It consisted of a few classics academics, a psychoanalyst who loved WWE, a boisterous southern orphan who loved Jacobean drama, a comedian-musician-video editor named Mark Prochazka who had worked for the infamous Sam Hyde, and Alexandre, my Québécois friend who went by the name “Palestrina” online after the renaissance composer. He loved critique above all things and I had told him he should direct this caustic rapier against others to gain traction. There were a few who were tangential to our group, like Kupps and a British satirist, and several other groups in the same orbital ring, but for the most part that was it. With tongue in cheek, we dubbed our circle “Noontide Twitter,” noontide being Nietzsche’s word, through the mouth of Zarathustra, for when the Übermensch would rise up, the event where “good” and “evil” were to be recognized as passing clouds over the expanse of a future humanity in which Dionysus would be fused with Napoleon and all bourgeois pettiness would dissolve.

When Hades’ Hatred was released, someone shared it in our group chat. It was so dumb, so below the mark it intended to hit, that we in our young bellicose nature could not look away or prevent ourselves from laughing. Everything about it—the name, the author’s name, the cover, every sentence of the preface—had us rolling. We started tweeting our jokes out, howling at its stupidity.

It wasn’t clear that the faceless lords of frogtwitter were invested in its success. While we thought it was just another one-off hack job by some irrelevant fool, like many of the things that would get posted and deleted by people using throwaway accounts, there was evidently a lot of planning and momentum behind the release, because the reaction to our response was apoplectic.

Even RAJ promoted the book, which challenged our respect for him. That was almost the worst part: seeing someone you admire tarnish their taste for ideological and political reasons, for the communal “frens” as they called each other, to go from the role of the hardened barbarian to the counselor of the hugbox.

From this point onward we could never again take the cultural Right seriously, in the present or in any of its past eras. Our uncritical honoring of ancient literature was dashed. Just like Harold Bloom with Harry Potter, something horrifying had turned up, the visage of the Epic Poem in 2018, the genre of “Homer, Virgil, and Dante” with whom Doomsday obtusely categorized himself: a hobbling, deformed clownshow of corny mythological references, shorn of all grace and difficulty, condemned to be a “God of War” rip-off. It dawned on us that this was precisely the nature of political Reaction itself: a suburban LARP, a goofy pageant, a graveyard robbery and a refusal to let sleeping dogs lie.

RAJ, perhaps humiliated, lashed out at us. He began orchestrating a conspiracy theory that Alexandre, the most vocal critic of the book, was a plant propped up by me, and that the think tank I worked for was giving him Koch Brothers cash to bring down the great powerful frogtwitter… This was hilarious to us, of course. I had no power, I was on Twitter out of boredom, not for work but precisely to escape from work, and our derision of the Doomsday book stemmed from a piety toward the promise of a real masterpiece for the “Right.” They raved for some time on this subject. More interesting is what led us up to this point, and what happened after.

I had first introduced my friend Alexandre to this world in June 2018, around the time I moved to D.C. We had been arch-reactionaries in the period of 2015-2017, so we understood all the arguments, but we had calmed down a lot due to a variety of reasons, primarily because we had come up against the limits of the very ideas themselves in light of the true face of history and the ironclad realities of the modern world. In fact, it was the dismissal of reactionary conclusions that was propelling our thought at that time: we found it highly productive intellectually to come up with alternative explanations for all the same phenomena highlighted by the reactionaries, and we’d take concepts from figures like Spengler and rework them to create an optimistic vision of the future. We found ourselves enjoying Nick Land’s Fanged Noumena writings, and everything we wrote to each other was in the spirit of pointing out how the online right-wing currents contradicted the yes-saying attitude of Nietzsche, whom they all claimed for their side, and how his works encouraged the utilization of the various failures of modern society to engineer a new renaissance. Nietzsche’s line, “The levelling of the European man is the great process which cannot be obstructed; it should even be accelerated,” was our rallying point during this time. Modern society’s downfall shouldn’t be feared; it should be used. Alexandre would message me things like “imagine if there was an Ur Symbol for many different things, like the infinitesimally small or the vast expanse of the sea; imagine if the entire concept of the “West” and its Faustian Ur Symbol is a fiction, and we could discover and activate or deactivate these cultural forces at will,” and I’d message back things like, “the globalist last men will be grounded up and used as protein power for the electric gods!” and things like that.

We started off with small, anonymous accounts and mainly just replied to users with large followings. We would post a few takes each day and slowly discover people who had good content and share them with each other. “Yo, this guy’s good, he’s like a Nietzschean who uses Madonna songs and 90s wrestling to get his points across,” Alexandre told me when he discovered Objet petit a, the psychoanalyst WWE fan. I’d send him the big accounts I grew to respect during the Trump election, and he got acclimated to how the website worked. Then August arrived and it was time for his wedding, but it was in Québec and I was broke and couldn’t afford the trip. This led to one of several falling outs we had over the course of our friendship. We didn’t speak for several months—during that period I went through a series of different jobs which is important but I won’t get into yet—but by the time I went to Kupps’ incel lecture we were talking again. Now Alexandre had amassed nearly 2,000 followers on Twitter, while I had deleted my account for professional reasons and had mostly ignored that section of the site while focusing on the news. He followed my professional account and started retweeting my posts, and soon I grew a following of all these crazy frog anons on a profile with my name on it. I figured it was already too late to go anonymous, so I just left it that way, and posted “clean” content about the authors I was reading, like Goethe, Emerson, and Spinoza, authors that were serving both as consciously selected forays into modernity-affirmation and as extensions of my previous Nietzschean leanings, “this-worldly” thinkers who I hoped would reveal a path forward for a this-worldly literature. Speaking through them and through a Darwinian-materialist view of life, I both critiqued modernity and strove to affirm it to mobilize a way out of it.

Above all things we had a dream to write a Supreme Fiction, a poem, or a some other kind of work, that would be so spectacular it’d blow the hinges off our world and make everybody pure and reverent toward Life. Alexandre and I had traveled extensively together and discussed this at length. We were both unhappy with the prospect of the future, and if it wasn’t for my girlfriend convincing me to move in with her I was planning to join the military or live in poverty just to escape the careerist 9-5 life. Alexandre was originally dead set on dropping out of college and coming down to New York where I was and working as a waiter in Brooklyn just to get away from his fate, but he too came to prefer the domestic life—for a time. While I was trying to find a good political job in D.C. to make ends meet, he was studying to become a scholar of ancient Greek—these were our answers to the question of how to make the concept of work bearable. But this was not a state of acceptance, more of a stalemate with the world; if we would not get to live as beat wanderers, we would cause a social revolution and remake the world according to our vision.

It felt like there was something so beautiful, so vast, so tremulously vibrant on the horizon that it was at times too much to contemplate directly. The more we talked about the unspeakable aesthetic grandeur of Marcello, or Joyce, or Titian, or the historical scenes described in Cardinal de Retz or Sallust or our favorite, Burckhardt, the more we would despair at the current state of things, and the unmitigated ugliness flooding in from all around us. Something had to give. Once we finished sculpting our words, and fashioned the perfect masterpiece, the lies on which our world was built would ring so hollow that it would all come crashing down and the Word would be unveiled with us at the helm.

The problem was, nobody seemed to fully grasp what we had in mind when we would talk about this vision. The longer I write about it, the more I hope it will come into focus. Perhaps it was all delusion, and we were just another failed band, and that is all that will come from this book. But I don’t think so. I believe there is something of note to pull out of this saga, like a concealed papyrus fragment wedged between two ancient stones.

Alexandre at this time would talk about “The True Sanskrit,” a phrase from a Novalis short story called The Disciples at Sais. “The True Sanskrit speaks only in order to speak, for speech is its joy and essence,” Novalis wrote. Alexandre repeated this ad nauseum, and wore it like a mantra for his outlook. At the peak of all his critiques, above all the rough crags and jagged spikes of his barbs against “bad taste,” was this True Sanskrit. It was the crown jewel of taste, it was this impeccable vibe that he traced in the best works of art, and it contained no message: it spoke to speak, simply and freely. In The Disciples at Sais, just as in the Schiller poem that preceded it, one of the students pulls off the mask of an ancient mummy only to find another veil. The point was that all inferior works of literature have some practical aim, some cause, some “social utility” or, like Harry Potter, bog themselves down in self-imposed bad taste while denying the existence of the sublime. The True Sanskrit, on the other hand, was an unabashed peal from a noontide bell, like the kinds described in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, that promised the future and redeemed the whole of the past, not because they “solved” anything or allowed us to transcend human life, but because they revealed what was already beautiful—perfect—in it, and allowed us to recognize the ebullient perfection of existence and dive into it.

In the face of all the ideologies that formed meta-narratives around life to explain its structural problems and offer engineerable solutions, the True Sanskrit sang: “O, friends, not these tones! But let’s strike up more agreeable ones, and more joyful!”

This “Sanskrit” was a baroque augmentation of the Nietzschean affirmation of life, a rewiring of the metaphysical categories of the brain to supplant both heaven and the atheistic void with this one life eternally repeating, a subject Alexandre and I had in our teenage years devoted much time to dissecting and applying to everything we observed and did. I have come to call it not the “Sanskrit” but the “Halcyon Tone.” The difference is small but substantial, as will become clear later.

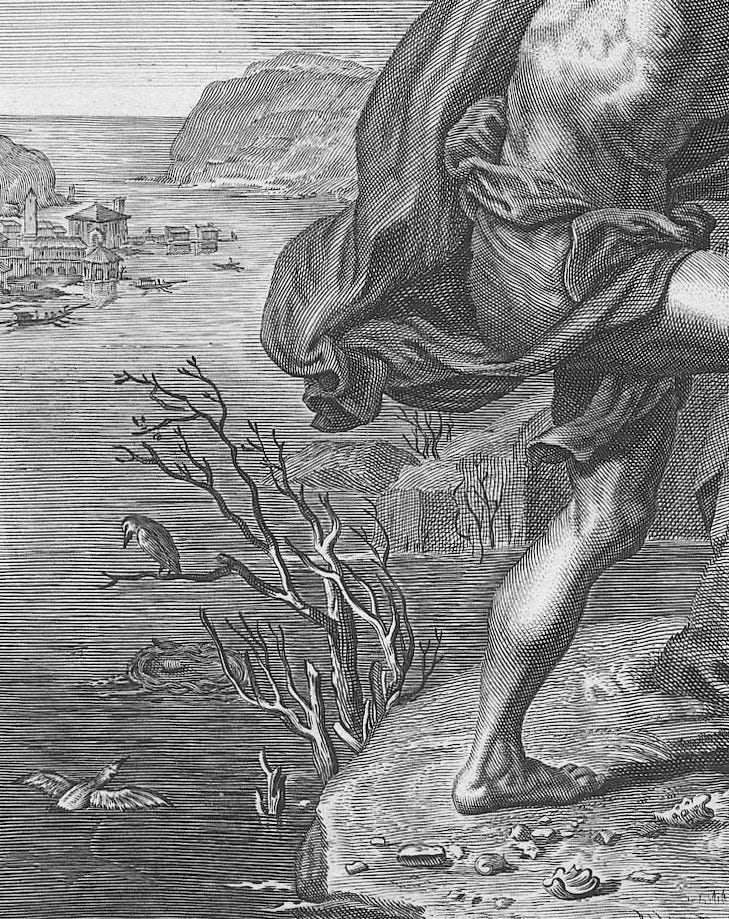

Alcyone was a Mediterranean queen whose husband Ceyx died at sea. Morpheus, the god of sleep, was pushed by Juno to reanimate his body and tell her of his demise. Alcyone, overcome with grief, drowned herself. As a gift for her fidelity, the gods transformed them into Halcyons, or Kingfishers. Alcyone’s father Aeolus, god of wind, calmed the winter storms once a year to allow her to lay eggs on the smooth surface of the sea.

The Halcyon represents the smooth perfection of the Mediterranean and its good weather—but more than that, it is another iteration of the dying and rising god, like Dionysus, Christ, or Tim Finnegan, and perhaps the most beautiful of all the myth’s versions. She is the eternal recurrence, brought on not by tragic intoxication, nor moral redemption, nor accidental injury, but amorous sacrifice: love not for the bloodless abstraction “man,” but for one specific man; and for electing to forfeit her life, for not clinging to a paltry shard of existence but instead having the surplus will to let go of it, she was rewarded with eternal life, with births and rebirths.

Nietzsche said his Zarathustra could only be understood if one heard its “Halcyon tone.” Its voice is not that of an ungainly systematizer or clamorous demagogue, but a brisk goddess with sweet music and quick feet.

This same tone reverberates through all history, and humankind performs its best deeds when it catches the tone in its works. I believe it was this tone that we heard, that we somehow uncovered through our actions, almost by accident—through the exploration and critique of everything that was not It. The identification of the tone was almost released to the world, but due to the Doomsday debacle and the implosions afterward it was left unheard.

It didn’t last because man is rarely satisfied with what he needs. La Bruyère says taste is the knowledge of when to stop—to know exactly where the point of completion is, no more, no less. The truth is, Alexandre, the great tastemaker himself, did not have the taste to pause here, but had to keep going, going, going … and the rest of the world followed him, with him or against him, into the cacophony of pitiless night.